A house for Mr Josettan

Summary:

A ad for paint offers a perceptive window into the life of north Indian migrant labourers in Kerala.

Josettan's house: Migrant labour in Kerala

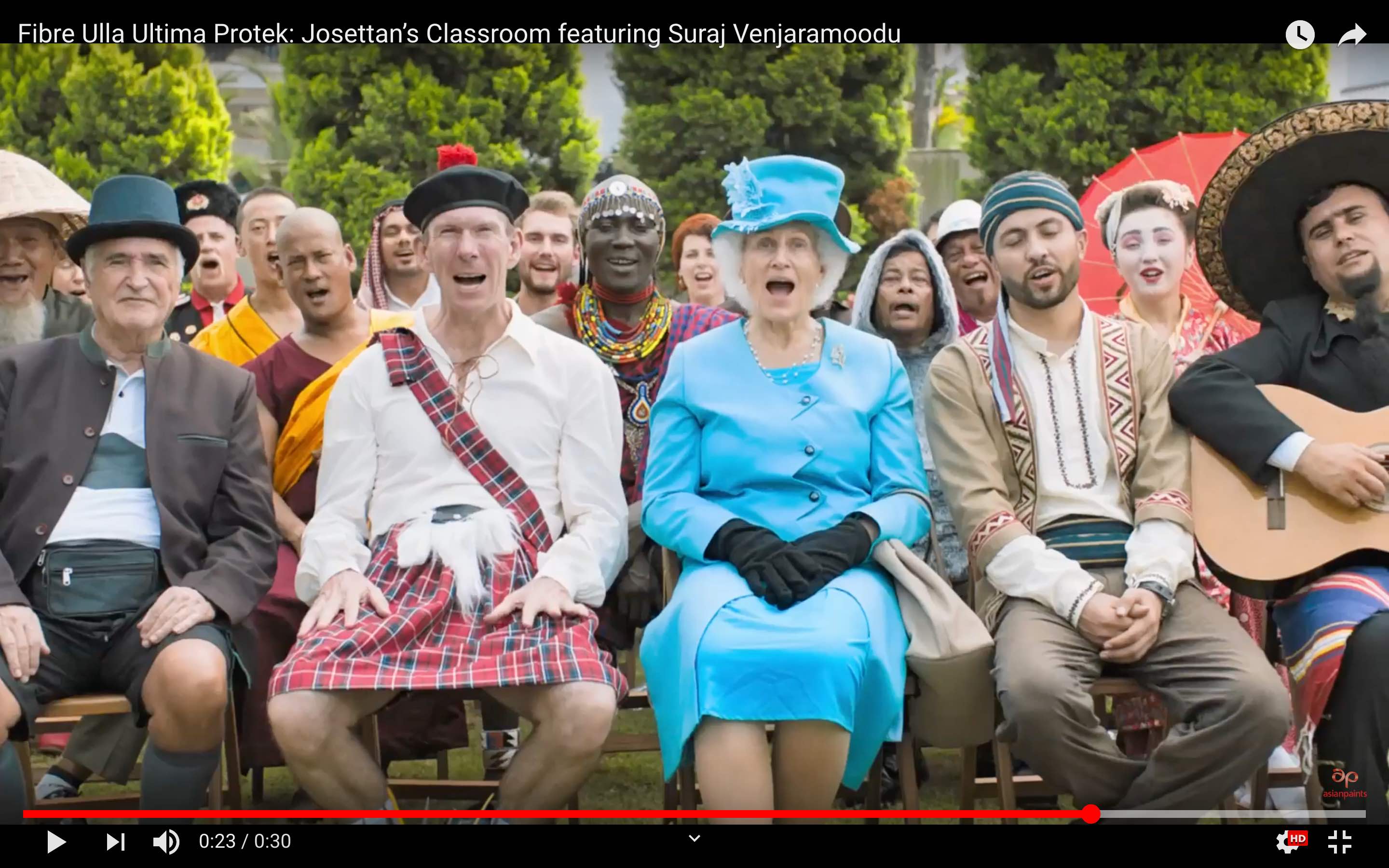

There's a new ad on Kerala's cable networks. It features a colourful, caricatured, bunch of foreigners visiting a house in small-town Kerala. Visitors include a 'Maasai' tribesman in full traditional get-up, a Queen Elizabeth-wannabe hat-wearing 'English' lady in a sky-blue outfit, a kimono-wearing 'Japanese', a 'Chinese' peasant in straw hat and a long dress, a 'Scot' man-spreading in his kilt, and a 'Mexican' strumming a guitar under the shade of his sombrero. They're in Thissur to see Josettan, and his house.

The ad portrays two categories of overlooked 'outsiders' in detail, obliquely revealing the cultural space and tolerance afforded in Kerala for such portrayals.

Africans in Kerala's popular culture

African characters do not make routine appearances in Malayalam movies or ads. Although the one-off white tourist of unspecified ethnicity sporting a thick British accent is a common trope, Africans are hard to find in Malayalam media. That said, the last major movie was 'Sudani from Nigeria'– the story of a young African footballer who comes to Malabar to play in the local 7 a-side football tournament. No other detailed portraits of African characters come to mind.

And yet, here's a mere advertisement, detailed enough to get a specific African tribe's name correct, and to translate the news about the protagonist's house in Swahili. 'Nyumba ya Josettan' is the title of a photo essay in the 'Maasai Times' newspaper which brought the Maasai tribesman to Thrissur in the first place.

It's charicatured, and might be one of the most famous African communities around the world, but the 'Nyuma ya Josettan' newspaper article points to a non-trivial amount of attention to detail.

Curiously, Americans seem to be absent from the assorted group of national costumes.

Here's the ad in it's full version

Portrayal of Bengali migrant labourer

The portrayal of the Bengali migrant in the ad is also notable. Our Maasai visitor, after reaching a major intersection in Thrissur town asks a Bengali migrant labourer for directions to Josettan's house. The migrant worker replies in a thickly accented Malayalam, 'Avide Setta', a corruption of 'Avide Chetta'. 'Chetta', a male honorific in Malayalam gets mangled into the 'Setta' of Bengali. The labour also has a Bengali newspaper in his hand, another nice touch of detail. I'm not aware of any Bengali newspapers circulating in Thrissur, but if they indeed do, that would be an indication of how deeply rooted out-of-state migrant labourers have become.

The attention to details is just a nice touch. Far more important is the fact that this ad got made and broadcast without any backlash at all– actual or feared.

Migrant labourers in Kerala and rest of South India.

Migration has been the core of the Indian condition for centuries. The 19th Century, the 20th century saw migrations following the partition. 21st century seems to be the period North to South migration. Between 2001 and 2011, the proportion of South Indian population reporting Hindi as their mother tongue increased by 40%, eclipsing the all-India increase of 25%.

The same trends have played out in Kerala, which has one of India's highest daily wage rates coexisting with India's lowest population growth rates. Between 2001 and 2011, Hindi speakers in Kerala almost doubled, albeit from small baseline of less than 1% of the state's population.

The similarities end there. In Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, the ballooning migrant presence has strained existing linguistic and cultural fault-lines, culminating in agitations against the use of Hindi in public places and travel systems. In Bangalore, none of the state owned public transport buses carry boards in Hindi. The older buses have signs exclusively in Kannada, while the newer buses have LED tickets for signs in English. In 2017, protestors blacked-out the Hindi names of metro stations in Bangalore, and in 2019, Tamil Nadu witnessed massive protests against an alleged imposition of Hindi.

However, the situation in Kerala could not have been more different. Both the government and the public have been accomodative and even welcoming of migrant labourers. Buses plying through major migrant hubs carry Hindi signboards as well as Malayalam. Children of migrant labourers regularly make the news during examinations for scoring well, including in Malayalam. The government of Kerala, launched an insurance scheme for migrant workers in 2017, enrolling over 150,000 workers. Under the scheme, workers would receive an insurance payout of Rs 200,000 in case if accidental deaths, and Rs 15,000 to cover treatment costs in private hospitals. The state government funded the scheme in full, with neither employers nor the labourers having to make contributions.

In Perumbavoor, a small town of 28,000 in the outskirts of Kochin, which has become a hub of migrant labour, shopkeepers and buses have signs in Hindi and Assamese. In Perumbavoor's Bhai Bazaar, thousands of migrant workers walk though alleys riddled with Hindi shop-signs, restaurants serving Bengali cusisine, and even a theatre playing Bhojpuri movies.

Explaining the difference: No easy answers

What explains this difference? What makes Hindi on signboards verbotten for Kannadigas, while a flesh-and-blood Bengali migrant in an ad aimed at true-blue Malayali home-owners goes unnoticed?

Did generations of emigration to the Middle East make Malayalis sensitive to the pain and perils of migration? Do they see a toiling friend or a relative in the Bengali or Bhojpuri migrant? Are they paying forward the helping hands they received during their Middle Eastern exiles?

Or is it because the migration so far has not threatened the dominance of Malayalam and Malayalis in their own states? Migrants from Bengal and Bihar are transient. They don't put down roots, nor do they occupy positions where they make decisions over the natives. In Karnataka, the anti-Hindi agitations arose from resentment against migrant bank employees who did not speak Kannada. The native Kannadigas often found themselves having to depend on these unhelpful employees for assistance. Kerala also has a smaller proportion of non-native population. Compared to Karnataka where Hindi speakers are about 3.5% of the population, Kerala's Hindi speakers amount to a mere 0.16% of the population.

As Kerala's population growth slows, migration of labour from Northern states will continue to grow, driven by the wage differential between their home states and Kerala. This can lead to hostility towards migrants, particularly North and East Indian migrants. However, the underlying theme of acceptance and assimilation highlighted through ads like the one discussed suggest a brighter future.